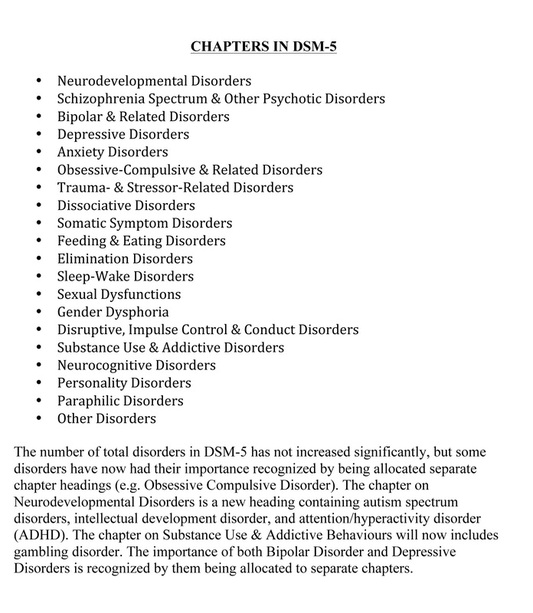

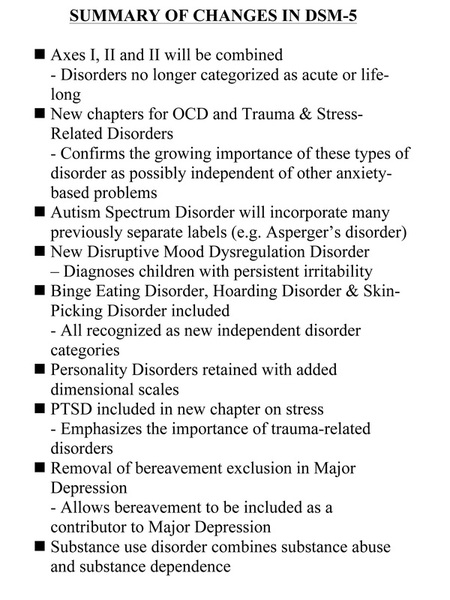

Specifically, if the APA want to impose a medical model on mental health then what will our doctors and physicians be learning about how to deal with their patients with mental health problems? The incremental implications are immense. It is not just that mental health is being aligned with medicine on such an explicit basis in this way, this issue is compounded by the fact that medical training still plays lip service to training doctors in psychological knowledge and, in particular, to a psychological approach to mental health. So has medicine taken the decision to align mental health diagnosis and treatment to fit the constraints of current medical training (rather than vice versa)?

I returned to a President's column I wrote in 2002 about the state of psychology teaching in the UK medical curriculum. The same points I made then seem to apply now. The medical curriculum is not constructed in a way that provides an explicit slot for psychology or psychological knowledge. Even though a recent manifesto for the UK medical curriculum (Tomorrow’s Doctors, 2009) makes it clear that medical students should be able to “apply psychological principles, method and knowledge to medical practice” (p15), there is probably no practical pressure for this to happen. Given that the ‘Tomorrow’s Doctors’ document does advocate more behavioural and social science teaching in the medical curriculum, I suspect that what happens in practice is that a constrained slot for ‘non-core medical teaching’ gets split up between psychology, social science and disciplines such as health economics. If a medical programme decides to take more sociology (because there are sociologists available on campus to teach it) – then there will be less psychology.

The second point I made then was related to the expectations of medical students. This was illustrated by a QAA report for a well-respected medical school. This made the point that:

“...there was a student perception that, in Phase I, the theoretical content relating to the social and behavioural sciences was too large. Particular concern was expressed about aspects of the Health Psychology Module....a number of students suggested that the emphasis placed upon theoretical aspects of these sciences in Phase I was onerous”

Well – death to psychology! My own experience of teaching medical students is that they often have a very skewed perception of science, and in particular, biological science. Interestingly, the ‘Tomorrow’s Doctors’ document advises that medical students should be able to ‘apply scientific method and approaches to medical research’ (p18). But in my experience medical students find it very difficult to conceptualize scientific method unless it is subject matter relevant – i.e. biology relevant. I have spent many hours trying to explain to medical students that scientific method can be applied to psychological phenomena that are not biology based – as long as certain principles of measurement and replicability can be maintained.

But there has been a more recent attempt to define a core curriculum for psychology in undergraduate medical education. This was the report from the Behavioural & Social Sciences Teaching in Medicine (BeSST) Psychology Steering Group (2010) (which I believe to be an HEA Psychology Network group). I am sure this report was conducted with the best of intentions, but I must admit I think it’s core curriculum recommendations are bizarre, and entirely miss the point of what psychology has to offer medicine! It is like someone has gone through a first year Introduction to Psychology textbook and picked out interesting things that might catch the eye of a medical student – piecemeal! For example, the report claims that learning theory is important because it might be relevant to “the acquisition and maintenance of a needle phobia in patients who need to administer insulin” (p30). That is both pandering to the medical curriculum and massively underselling psychology as a paradigmatic way of understanding and changing behaviour!

Medical students need to understand that psychology is an entirely different, and legitimate, method of knowledge acquisition and understanding in biological science. Not all mental health problems are reducible to biological diagnoses, biological explanations or medical interventions, and attempts by the APA to shift our thinking in that direction are either delusional or self-promoting. What is most disappointing from the point of view of the development of mental health services is the impact that entrenched medically-based views such as those of the APA will have on the already introverted medical curriculum. Doctors do need to learn about medicine, but they also need to learn that mental health needs to be understood in many ways – very many of which are not traditionally biological in their aetiology or their cure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed